Help

Until a few years ago, Mandarin Chinese was surrounded by an aura of mystery. It was considered an exotic language, undoubtedly difficult to learn. Foreigners as well as the Chinese themselves thought that mastering Mandarin Chinese was indeed an impossible goal to reach. Then came Dashan.

In this short documentary, it is shown how Dashan shocks the audience by speaking flawless Chinese on a TV program watched by half a billion people. As a result, Dashan becomes an instant celebrity in China.

Many things have changed since that distant 1988, and the number of foreign students coming to terms with the Chinese language and living in China has grown dramatically over the last 20 years. It is no longer unusual to come across a “wairen” (foreigner) in Mainland China. Yet, many students keep having problems when it comes to speaking Chinese, and this is mainly due to an aspect often considered “dramatic” from a Westerner’s perspective: Chinese tones.

When it comes to speaking about tones, two things immediately to mind:

1) Why are Chinese tones perceived as being so difficult?

2) Is there a proper way to learn them?

Let’s address the first issue. It is important to emphasize, once again, the following point:

Chinese is a tonal language. This doesn’t only mean that tones make up the words, but also that the meaning of the words themselves relies on their tones.

In non-tonal languages such as Italian or English, tones do exist. We are not aware of that simply because the meaning of the words does not depend on their variation. So, in theory, the same tones can be used to visually represent syllables that make up the words in non tonal languages.

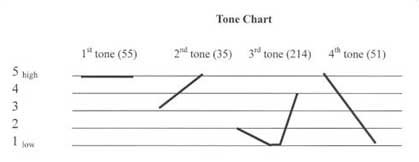

The very first thing you’ll be confronted with when it comes to speaking Mandarin Chinese is the tones. The following charts show, in detail, the four “heights” of a syllable in Chinese.

Now, imagine that you want to learn Italian, and that your teacher imposes the aforementioned bottom-up approach. So, one should start from the sound quality of syllables and then move on to words and sentences. After tedious explanations and charts, imagine practicing the following sentences:

Ma che hai fatto oggi? ==> Mā chē hā-ī fàt-to ŏg-gí?

Ma dove sei andato? ==> Mā dō-vē sē- ī ā-ndàtó?

Imagine the gigantic effort in trying to utter a whole sentence by looking at the tone of every single syllable. Things get even worse when it comes to thinking about a sentence, in that one should also remember every single tone!

La pōlĕntá* è un cibo tipico dell’Italia del Nord. (‘Polenta’ is a typical dish of NorthenItaly)

Mi piace la pōlènta.* (I like ‘polenta’.)

As you can see, the word “polenta” at the beginning of the sentence sounds like a first-third-second tone, while it becomes a first-fourth-fifth (neutral) tone when at the end of a sentence.

It is obvious that this approach to learn Italian would be a disaster. None, fortunately, would dare adopt such an approach. Yet, even considering the big difference between Italian and Chinese, this IS the only approach adopted in the vast majority of Chinese courses, be it at university or in private schools. Now, is there an alternative to all this?

Very often the combination of Chinese tones and characters causes a lot of students to give up too soon. Yet more than one and half billion Chinese, as well as a vast number of foreign students speak impeccable Chinese, showing that Chinese tones are not impossible to learn.

We often tend to see children as the best and fastest language learners, and attribute their success to a brain plasticity and flexibility that we adults no longer possess. One might quibble with the definition of “brain plasticity”, but a key factor in the learning process is often omitted: the way they acquire a foreign language is different from ours.

Children hear whole sentences. They don’t start with syllables. They simply hear chunks of a language and then identify the single components by themselves. As adults, we tend to think that we can figure out the structure of a language by analysing every single aspect of it, and we lose sight of the general, broader picture. As adults, we still have the capacity to hear, but we have partially lost our capacity to listen.

In order to restore this capacity one needs patience and a bit of open-mindedness.

Only a few months after starting learning Chinese “the traditional way”, I realized how important it was to listen to whole sentences. This thought dawned on me when I first used a special software in which a native speaker utters a sentence, and you have to repeat it. The software program then compares both sentences and gives you a mark ranging from 1 (very poor) to 7 (perfect).

Even though this was a machine with all its flaws, the exercise was fun and interactive, and before I knew it, I had tried more than 300 hundred sentences this way. I was repeating sentences without even thinking about tones.

Based on my experience I would suggest that one follow these simple steps:

1) Read the introduction on phonetics: it is always helpful to know that Chinese is a tonal language anyway, and that it has 5 tones (4 + a neutral one). This will always be a good reference. Furthermore, at the early stage, one should learn immediately how to pronounce consonants, taking special care in differentiating retroflex consonants (such as zh, ch, shi) from normal ones (z, j, s), and aspirated (p, t) from non aspirated ones (b, d).

2) Once you have a general understanding of Chinese phonetics, start considering very simple sentences. Listen to the sentences dozens of times, and repeat them with your eyes closed, without looking at the tones that make up the individual words.

3) Then consider the individual words, and try to focus on them when they are “embedded” in the sentence. If necessary, write down a list of the words as long as you learn them.

4) Move on to more complex sentences (main clause + relative clause/conditional clause, etc.)

In addition to the tones, it is important to point out that Chinese also has a general pitch (the way a sentence flows) which has to be taken into account. There is a very interesting video on YouTube by my friend Marco on this subject.

1) Finally, after having learned how to listen, you have to simply… start listening! Do this at least half an hour a day, preferably an hour, and when you are ready, try to spend even more time on this activity. It is key to speaking native-like Chinese. Starts with audio AND the corresponding script.

Quality at the beginning followed by quantity at a later stage is a great way to reach an excellent pronunciation!

The tones of Mandarin Chinese are undoubtedly a challenge, but they can be learned with the proper approach. The one I propose is simple: consider a whole sentence and listen to it, try to figure out how it sounds as a whole without focusing on the tones. You’ll find that it is an efficient approach to acquiring tones in a natural way.

(*) In 2006, Harold Goodman, author of three audio courses created an approach to color-code Mandarin tones. In addition to colors, each tone has also an accompanying gesture. For example, for the sound ā your thumb moves in a straight, lateral direction, index finger points upward for á, The index and middle fingers form a V sign to indicate the third tone (ǎ), and so on. This approach was tested with volunteer students in theUS and they seemed to recall tones very well.

For more information, please refer to:

- http://www.michelthomas.com/learn-mandarin-chinese.php

- MANDARIN_CHINESE.pdf

Written by Luca Lampariello

Related topics:

- How to Learn a New Language: Start with the Right Resources

- Start Chinese: how?

- How to practice English every day while staying in Paris?

- DOES DRINKING HELP YOU SPEAK A FOREIGN LANGUAGE?

- How to Learn the Korean Writing System in Just a Few Hours:

Comments

1

1

3

All

3

All

| vincentOctober 2013 Thanks Luca for those useful tips !!  PS : Danshan makes me want to give up Chinese !! too good  |

English

English

Source: Luca Lampariello

Source: Luca Lampariello