Help

According to this belief, the language you grew up with is often a form of “negative interference” when trying to acquire new ones, and so it is best to avoid this interference altogether by keeping native language use to a minimum.

To this end, we see many learners committing themselves to Skype conversations that are 100% in their target language, creating image-based flash cards, and even using single-language dictionaries, where definitions of words are not translated, but are explained in other words in that same language.

Such non-reliance upon translation from or to one’s native language is certainly a worthy goal—and the above methods are good ways to go about it—but when I see learners go to such great lengths to avoid translation on principle, I can’t help but get the feeling that they are avoiding something that potentially could be a great benefit to them.

Why Translation Gets No Respect

Of course, it is not the fault of the learner that translation is so maligned a concept nowadays. One of the foundational methods of foreign language teaching, known as the Grammar Translation Method is still synonymous today with endlessly reading and rewriting mindless sentences from one language into another, in order memorize grammar rules. This method of defining words and phrases in one language by comparison with another has purportedly been around for hundreds of years, and is still the method seen in many textbooks today. The downfall of this perhaps most traditional of traditional methods is not that it is ineffective, but that it is often dreadfully boring.

Other methods were later developed in an attempt to introduce something more dynamic to the language learning experience. In particular, a method known as

Translation Will Always Be Necessary

As well-intentioned as

And this is exactly why drawing connections between your first language and your target language can be so useful. As an adult speaker of a language, you have an advantage that no “critical-period” age child could ever have: you possess an entire mental database of interconnected concepts, memories, and life experiences that have already been codified into a single language. As such, you don’t need to re-learn the concept of love when you learn it’s corresponding word in another language. With the help of translation, all you need to do is associate the native word—love—with the new word—say, amore—and the job is essentially done.

How Translation Can Reveal a Language’s Secrets

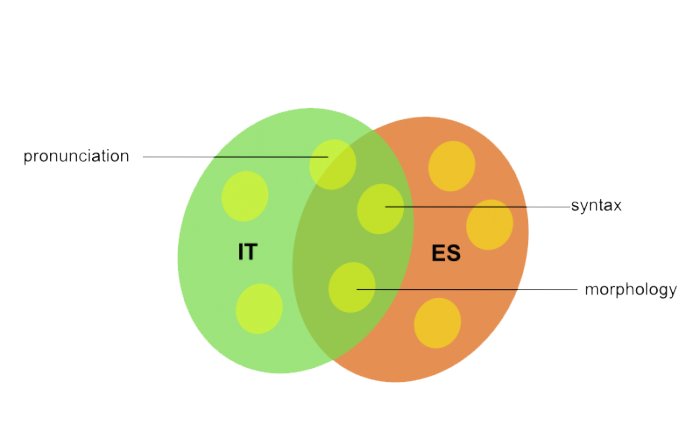

Translation is a necessary and useful part of language learning because it can also reveal important details about how two compared languages operate.

For example, any human language has the capacity to express the following idea:

I’m going to the beach with Maria, because today it is very hot.

Despite the fact that this phrase can be expressed in any human language, the syntax and vocabulary used may vary greatly from one language to the next. These variations, dependent on the distance between two languages, can only truly be revealed through translation.

(I go to beach with Maria, because today does very hot)

(I go to the beach with Maria, because today does very hot)

Comparing these phrases through translation reveals that the vocabulary and syntax of the two languages correspond on a near one-to-one basis.

In this situation, a native speaker of Italian who is learning Spanish (or vice versa) could benefit greatly through regular use of translation, because both languages are so similar to one another.

(I go to beach with Maria, because today does very hot)

(I want to-the beach with Maria, because it today very hot is)

Translating between these two languages reveals that they are structurally different, but contain some similarities in terms of vocabulary and word order.

In this scenario, a native speaker of Italian who is learning German (or vice versa) would have some difficulty in translating from one language into the other. However, he would still benefit from translation, as repeated exposure to the syntactical differences will help him to internalize the patterns of the target language.

(I go to beach with Maria, because today does very hot)

Kyou wa totemo atsui kara, Maria san to umi ni ikimasu.

(Today very hot since, Maria with sea to (I) go)

Here, the problems that we saw between German and Italian have been compounded. Japanese and Italian have completely different word orders, and they do not share any similar vocabulary.

Here, a native speaker of Italian who is learning Japanese (or vice versa) would have much difficulty in directly translating from one language to the next. As with German, however, a regular “training regimen” of translation from and to both languages would serve any learner in deciphering exactly where the syntactical and lexical differences lie, and eventually help him or her to memorize the mental operations needed to “turn” an Italian phrase into a proper Japanese one.

– Why translation is a necessary part of language learning.

– How translation can help you determine the syntactic and lexical relationships between two languages (among others).

Now we just need to discuss how, exactly, you should go about incorporating translation into your own learning routine.

The Right Way to Translate

As I mentioned before, translation is a tool that can reveal to you how two languages convey a single message in completely different ways.

Every thought conveyed through language must be manipulated and re-organized by the semantic, syntactic, lexical, and morphological rules of that language before it can be reborn as a correct, grammatical sentence in that language.

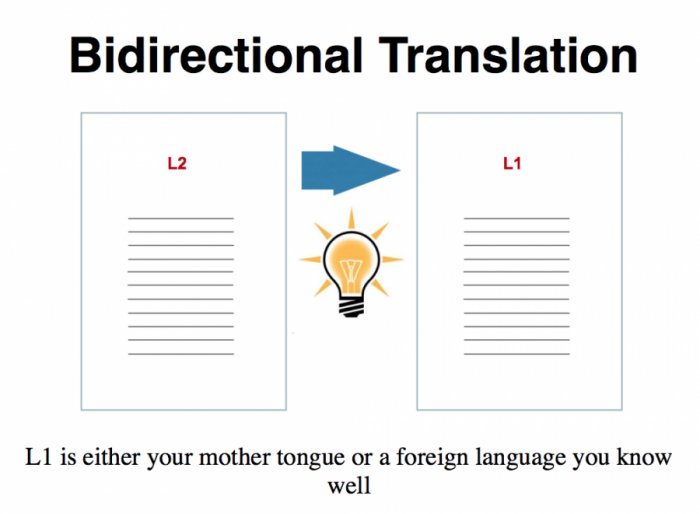

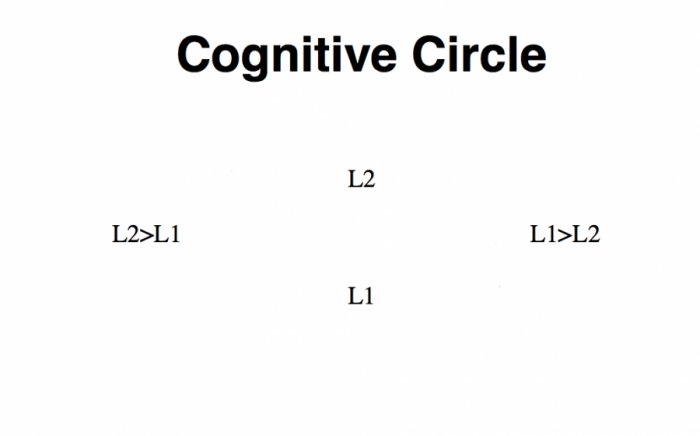

To truly familiarize yourself with these rules in both your native language and your target language, it is essential that you engage in a technique that I call “bidirectional” translation.

That is:

1. Translation of a L2 (target language) text into your native language. This is done to help you fully understand the content of the text.

2. Retranslation of your “new” L1 translation back into L2. This helps you correct your own mistakes, see gaps in your comprehension, and to think the the target language.

Of course, don’t just go around completing bidirectional translations of any texts that you can find. You want to devote your translation time to texts that are:

– Short (between 100-500 words)

– Interesting to you

– At or slightly above your level of proficiency

Such practice will be of particular benefit to you during the initial (pre-intermediate) phase of learning a language, as you will gain familiarity with the most common structures of your target language more quickly and easily.

Use the Tools Available to You

My hope is that this article has shown you how your mother tongue can be a huge boon to your language learning, instead of the hindrance it is often seen to be.

The key to using your mother tongue effectively is through efficient application of bidirectional translation, whereby you translate and retranslate short, useful texts back and forth between languages in order to master the internal structures of your target language.

Remember to start simply. Learn how to turn short phrases in your target language into your native tongue and back again, and then move on to the more difficult, the more challenging, and the more complex. With time, you’ll find that no matter what message you need to convey in either language, you’ll be able to communicate the message holistically, rather than word by word. It is at this point, when you’re no longer stymied by the mental acrobatics of target language grammar and syntax, that you’ll truly be able to begin mastery of the language.

If you’re interested in learning more about my bidirectional translation method, I’ll be discussing it in further detail during my talk at the Polyglot Conference in Thessaloniki, Greece on 29 October 2016.

Stay tuned and happy language learning!

Written by Luca Lampariello and Kevin Morehouse

Related topics:

- How do I use Russian cases?

- How to speak like natives with a real English accent?

- Why find a passion for learning languages on the internet?

- How to learn Russian

Comments

1

1

1

All

1

All

Source: Luca Lampariello and Kevin Morehouse

Source: Luca Lampariello and Kevin Morehouse